Blockchains as coordination systems

What’s the value in an incentive system that aligns people? What’s the value of uniting people towards a common cause?

Big questions, involving politics, economics, organisational structures and more. Laura Lotti explains how blockchain tokenisation is opening up new ways to do these things. Tokens are tradable like currency but also runnable like programs, and because they’re both at once, they offer new ways of organising people.

We can start by looking at tokens as software with explicitly defined interactions, like buy (join), sell (leave), stake (commit) or vote, but instead of representing ownership, they define rules for people to self-coordinate around a common goal.

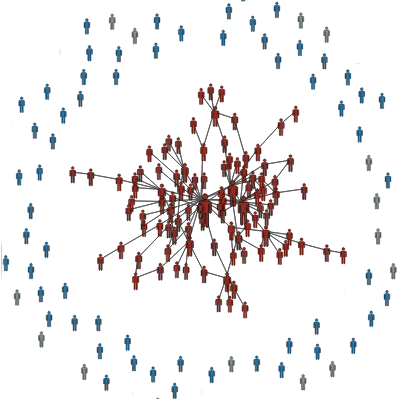

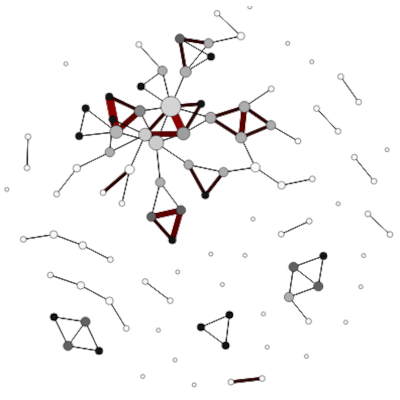

This makes DAOs a new form of human coordination. Not because they’re decentralised, or because they’re open. (Those have happened before.) DAOS are a new form of human coordination because they align people using blockchains.

This creates a new kind of relationship between DAO participants which we’re still learning about and evolving.

We need to be careful about what assumptions from the our current mental models block us from understanding something new.

If someone never saw a plane before, they’d ask:

” What kind of bird is that?”

or maybe

“What kind of train is that?”

And we could call a plane a bird-train, but we’d really be missing the point.

We wouldn’t get far trying to understand planes if we kept thinking of them in terms of birds or trains only. Clearly, something else is going on.

With token economies, we still have an economic system, but it isn’t a corporate one or even a commercial one. Our ideas of shares, ownership,control, employment, of exchanging labour for money, or even investing capital for personal gain – they don’t quite work here. Something else is going on.

What tokens enable isn’t just a tradable currency or cloud computing. They attract a group of people around a common goal, and align them with a hard-coded incentive system. When you buy a token, you trade capital for participation in that token community according to how it’s programmed. So yes, it’s a tradable currency and code running in the cloud, but it’s something quite different from both.

Because that code isn’t owned by anyone, it’s now just something that runs forever as long as that blockchain runs. Your token doesn’t give you shareholder or ownership rights to that code (or anything else), it gives you tokenholder rights to participate. (Those rights are different for every token.)

And we can see a common mistake when people buy and sell tokens, thinking they’re somehow buying “shares” in something. They’re not shares in the same way stocks are shares of ownership in a company.

What tokens and stocks have in common is:

In the case of stocks, the price of the stock goes up or down based on how much potential that owners and potential owners see in that company. In the case of tokens, the price fluctuates according to how much potential its participants or potential participants see in the coordination system it provides them.

The value in a token is largely connected to the community it attracts, normally around a common goal. So how does a token claim a hold on the value of this community?

When we see a handle on something, we assume its liftable. When we see something small, we think it’s light enough to lift. When we see a switch on a wall, we know that probably controls the lights.

In design and cognitive science terms, when a property of an object (on environment) tells us we can manipulate it, that’s called an “affordance”.

In the case of digital objects, the app allows us to manipulate something economic, so it’s an “economic affordance.”

A light switch is a physical object, and an app in a phone is a virtual object. And yet, we learn that these little boxes on our walls or on our phones give us deeper reach.

In the same way we know light switch controls the movement of electricity (effort) through wires and bulbs (resources), we know that a ride-sharing app will mobilise a driver (effort) and car (resource) to come pick us up.

Digital objects, as economic affordances, only exist when enough humans agree to interact with them. If the drivers didn’t agree to participate and your friends didn’t think of the app when they wanted to go somewhere, that app wouldn’t do anything. So it wouldn’t be an object in anyone’s mind.

Once we all start to agree on how this thing works, it becomes a new type of object, and “affords” us control of effort and resources.

So something as simple buying and selling a token becomes like a light switch. It’s a new type of economic mechanism that we get to experiment with.We can start plugging it in to different functionality.

With tokenized communities, people align to a common goal, a North Star, without being an owner, employee or shareholder. It’s an economic alignment around a new kind of virtual object that is neither company or app.

We can look at tokens as participation rules laid out as economic incentives, and realise we may not even need human managers to coordinate us. Coordination through well-designed token economies reduce the need for hierarchical leadership and middle management because the incentives move people towards self-coordination rather than managerial coordination.

Attracting people around a common goal isn’t new, but coordinating them with a tradable and functional token is very new. And that’s worth something because that coordination mechanism enables us to achieve goals that matter to us, especially goals that the old forms of coordination (like companies, NGOs and governments) are not good at. We are all aware of the downsides of corporate behaviour, poor NGO success rates, and government incompetence. Well, blockchains and DAOS add a new tool to this toolbelt.

We’ll leave you with Lotti herself, explaining why we value these systems, even at the start, even before they’ve done anything:

Thus, while cryptotokens’ underlying value at the time of issuance and until realization remains unbounded – structurally, it cannot be known in advance – by definition each token is paradoxically fully backed by its functionality, or, in other words, by what it potentially affords.

Each token has value because it’s backed by a coded ruleset that each of it’s holders has agreed to. So in the same way a publicly-traded company is valued by it’s future potential, the value of the token is the valued on the potential coordination it can deliver.

While these are some big ideas, they give us very simple rules in DAOS: